Remote Simposium

Remote Simposium

I take a lighthearted approach to wine. I like to drink it without speaking, to merge with the red fluid in my glass and abandon myself to pure oblivion. I drink and think of scarlet wine as if it were the water of the river Lethe, forgetting all else as I sip. I love drinking wine and only wine because among all the liquids that induce inebriation it alone brings me closer to the sense of ambrosia, to apathy, to a taste of Dionysian intellectual style. Only wine is so sincere that it leads to dreams so hypnotic that they bring out the truth and keep doom at bay. As long as the wine is healthful, of course. This is how I feel when I know that the wine of Luca Sanjust is arriving. He alerts me and I station myself in the house. I don’t go out as I await the delivery. All excited, I anticipate the pleasure of opening a bottle. And when I open the bottle, I say to myself: it really is true: “in vino sanitas.”

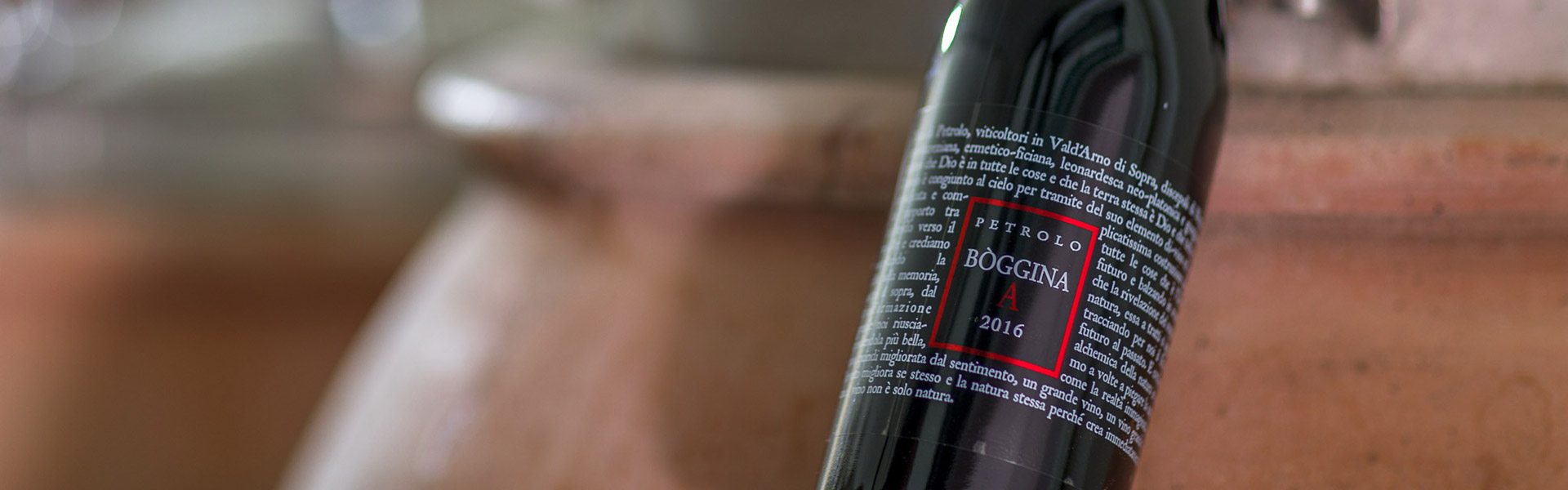

The first thing I do, even before uncorking, is examine the label. I need to remove the cork, but that always takes a bit of time because the label catches my eye. By now I know it well, but I reread it anyway. I surrender myself to the romantic vortex of the tutelary deities hovering in the glass. Bottles of Bòggina (which are three: A, B and C—a Sangiovese, a Trebbiano, another Sangiovese) carry a testament to identity. Sanjust provides a precise declaration: his wine is produced following the philosophical furrows carved out by Heraclitus, Dionysus, Epicurus, Lucretius, Ficino, Leonardo, Giorgione… Of course, I should go to Sanjust and not he to me sub specie alcolica. I should go to Val d’Arno di Sopra, to Bùcine. I should chat with him, be enlightened, see and smell the soil and the vines. But with this devil of a disease, I can’t. I shall wait, limiting myself to reading the label and continuing my remote symposium.

“Oinos kai aletheia,” I tell myself, and like a good symposiast I focus on the philosophers. I am convinced that their being there, on the labels, reveals everything. Leonardo, the penultimate member of Petrolo’s Hermetic family, used to say: “Much happiness be to men who are born where good wines are.” If that is so, I understand why I am so entranced when I drink. And I imagine the bliss I will feel when I trace the wine in my glass to its roots… I am more and more convinced that the nomenclature on the label can tell me everything I need to know. And I don’t worry about Mario Soldati’s view that if women fail to understand wine it’s the fault of the men who indulge them in every facile charm, above all that of the labels. Sanjust bewitched me with his. After all, he admitted on his website that he is the heir of Nepo di Galatrona, the prodigious sorcerer of the fifteenth century. Convinced that I’m falling victim to a magic spell, I read and reread the formula affixed to the bottle. Sooner or later the night will really pass, the disease will be eradicated, we will be able to go to Bùcine. While I wait, I have a last drink and look at the photos on Petrolo’s wonderful website, dreaming about sleeping in the villa a few steps away from the Tower of Galatrona, while drinking a glass of Merlot.

Petrolo’s world is irresistible. And yet I get the impression that those long-necked dames of bottles don’t care to be understood; they’d rather be consumed. I’ve received many of them in recent months, and they have been a bit like cherries: one bite led to another. Also because, as Soldati himself and Camillo Langone (my master of literature and wine) taught me, every bottle is unique. Every bottle is a human being, or rather a man, or rather a woman, or rather a diva, as Langone says quoting Rabelais: “The truth is hidden in wine. The Diva Bottle sends you there.” In short, each of them tells an individual truth, because in wine the variables are infinite, every result is incalculable: wine changes until the last moment before uncorking… It never stops. We would have all the elements to talk about oenological theology, maybe about each bottle’s exceptionality. Each belongs to a family of thousands of twins, but just as twins have different characters, so they are unique pieces. They are works of art in spite of serial containers. Sometimes they are absolute masterpieces, like Sanjust’s Bòggina A.

The wine, he explained to me via email, wants to merge with the drinker: two make one. So I thought that it cannot be a coincidence that the summit of the writings on love is unraveled on the set of a symposium… And that the expression “di due fare uno” is the child of Socrates’ ethylic dream… And that the plot of the ethylic dream is entrusted to a woman, Diotima of Mantinea… This hypothesis that the bottle is feminine is reinforced by the energy that woman and bottle share. The vitality of bottles pushes to the maximum the process of continuous transformation that wine desires and requires, pushes as if she were the mother who ultimately gives birth and life to wine. This wine that wants to invade and flow within us, that seeks in us its ultimate, definitive guardian… It is a wine that is alive, healthy, true, and not content to be understood: it wants to be seized, poured, drunk. This wine seeks eternity, continuing to exist in the body and mind of its drinker. Wine that flows as everything flows, fast, strong with the inexhaustible force of Heracles. I think this and much more every time I read the magic formulas on the labels of Bòggina. But now let’s put away the enchanted container, and move on to the contents.

The wine I prefer, no doubt about it, is the Sangiovese in amphora. Sanjust, munificent and wise, has just sent me a dozen examples of Bòggina A. I particularly adore it because it is a wine that gracefully explains the difference between old and antique. The old is a relative of the ugly, unlikely to return to vogue because—senectus ipsa morbus—it is destined to die. By contrast, the ancient never dies. The amphora that has been the treasure chest of ecstasy for the last eight millennia never dies; it was conceived for preserving matter in its dark womb. The amphora gives substance to the palingenesis of Georgian, Greek, Etruscan and Roman wines. Palingenesis, in fact, authentic reincarnation—this wine is redolent of Orphism—reincarnating in our glasses an ancient wine, yes, but not an old one. Remote and perfected, a jewel of Etruria. This option of Sanjust excites me more than any other. The amphora is the most natural of mothers, the most magnanimous, the most archaic. It does not overpower the child it carries inside with its odors, its flavors, its ambitions. The amphora prefers wine of oblative love. It is an aristocratic mother—maybe that’s why it so pleases Sanjust—because like every celestial spirit it lets others be as they are. And the wine I am drinking tastes alive, it tastes healthy, it tastes true. It is a wine that knows itself. There is no trace in my glass of bourgeois leftovers. Rather, I sense the intense scents of earth and nobility. All those deities of the labels, male protectors of female bottles, find a stable home in this wine. Drinking the Sangiovese in amphora, I am convinced once and for all of what was written by Guido Ceronetti: “Wines, like poetry, cannot be democratized.” Bòggina A refuses the tyranny of any demos.

I do not know when I will ever breathe the air of the vineyards of Val d’Arno di Sopra. With my senses and philosophy complicit, I wonder if I will imagine the amphorae filled with nymphs when I am there, or of the Bacchantes hiding in the mountains. If I will surrender for a moment to the spell of pantheism. Or if I will think of the all-embracing universe. I wonder if I will be twisted by the spirals of the cosmos. Or if, as Sanjust hopes, I will fall at the feet of the entire world. Who knows? For now I know that real wine is nature that becomes culture, soil that becomes style, goodness that makes you blissful.

Confined as I am, I have decided to select Epicurus among my favorite teachers, and hold on to the most natural of pleasures. One day, perhaps, in the Val d’Arno di Sopra, we will sing together: “We of Epicurus are the priests / … / And we’ll raise the canticles of Bacchus to heaven.” (Lorenzo Stecchetti).

Waiting for the universe to heal itself, we serene drinkers, halfway between nature and culture, with our glasses held between our fingers—a gesture of civility—we speak by sipping, far from the world’s dramas.